If you're looking for an educational outdoor summer getaway, the birthplace of American Forestry, "The Cradle of Forestry," near Asheville North Carolina is definitely worth the trip (and within driving distance for much of the Southeast). Forester and local, Jim Mize, shares the captivating story behind this historic destination.

The birth of forestry as a science in America is a story with well-known characters, such as Theodore Roosevelt, George Vanderbilt and Gifford Pinchot, as well as one largely forgotten gentleman named Dr. Carl Schenck. It’s a story of rivalries, misfortune, and perseverance.

The story begins with George Vanderbilt in 1892

When Vanderbilt inherited a portion of his father’s railroad and steamboat fortune he decided to construct his own estate in western North Carolina. He purchased 125,000 acres of woodland with the goal of building a self-sustaining estate; known today as Biltmore Estate.

A view of Pisgah Forest from the back of Biltmore Estate

With over 100,000 acres of timberland to manage, Vanderbilt turned to Gifford Pinchot, one of only a few trained foresters in the United States.

Pinchot had studied forestry in France. At that time, no forestry schools existed in the U.S. so anyone wanting to pursue a forestry degree went to school in Europe. Pinchot spent the next three years developing management plans for the Biltmore Estate. He had begun to implement them by 1895 when he decided to go into consulting.

This left Vanderbilt in need of a replacement; he turned to a German forester named Dr. Carl Schenck.

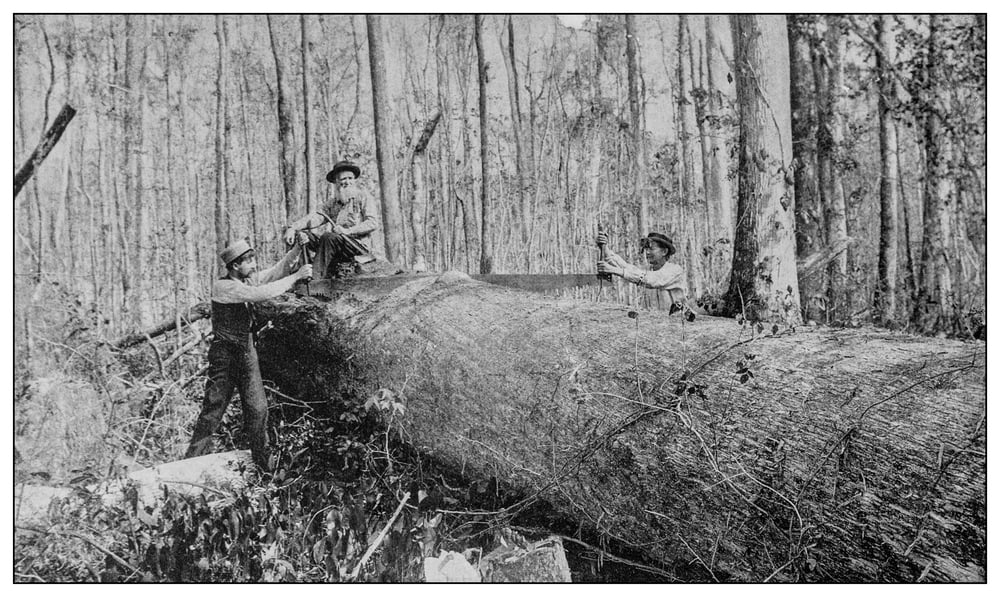

Schenck quickly learned that not all of his forestry education transferred to his new country. For instance, he inherited Pinchot’s forestry plans and projects including one to move poplar logs down the mountain to market. Without roads, the most common approach back then was to build splash dams, let the water back up, release it and float the timber downstream in the surge.

Schenck quickly learned that not all of his forestry education transferred to his new country. For instance, he inherited Pinchot’s forestry plans and projects including one to move poplar logs down the mountain to market. Without roads, the most common approach back then was to build splash dams, let the water back up, release it and float the timber downstream in the surge.

As Schenck wrote in his memoir, Cradle of Forestry in America, “forestry was a problem of transportation and that transportation was a problem of topography.” Imagine trying to move 17-foot logs miles through torturous creekbeds with enough water to move the logs and not so much that they bound along out of control.

His first splash dam project was on Big Creek which fed into the Mills River and was a stream with too little water normally to float logs. So they waited for rain to augment the flow.

His memoir sums up the escapade that followed.

“When they came (the rains), my worries were hugely increased. Logs were spilled over the fields framing the Mills River; riverbanks and bridges were torn; farmers along the river were furious, and my crews were forbidden to enter upon their premises, where many logs were stranded and scattered. A very rat tail of lawsuits was the consequence. . . Vanderbilt was compelled either to pay the bills for damages presented by the farmers or go without the logs.”

“When my logs rescued from the Mills River arrived in the French Broad, that river did not have water enough for six months to float the logs to the mill in Asheville; and when the rains and the freshets came, they were so wild that many logs dived beneath or jumped the boom and were routed for the Tennessee River and on to the Mississippi!”

These experiences left Schenck a fan of roads. By 1905, he had built over 80 miles of road in the Pisgah Forest at a cost of $40,350.

Old fashioned moveable sawmill.

The other need of good forest management was good foresters

Schenck began by taking on apprentices and from this experience the idea of a forestry school germinated. The Biltmore Forest School was officially founded in 1898, the first such school in the United States. It was soon followed by a graduate forestry school at Yale and another four-year school associated with Cornell.

Rivalries developed both in forestry philosophy and competition for students.

In 1905, Roosevelt appointed Pinchot to head the United States Forest Service. Both promoted this new field attracting students and spawning forestry associations. Pinchot advocated for Yale, classroom education and public forest management in contrast to Schenck’s forestry school, mix of class and field education and private forest management.

Classroom at the Biltmore Forest School.

At one point, the rivalry grew to the point that Pinchot wrote to Vanderbilt recommending the closure of the Biltmore Forest School as it didn’t conform to his views. Yet Schenck’s school was turning out students who found employment in industry and even in Pinchot’s own bureau.

Forestry filled the days of Schenck’s students

Most rode to school on horseback and attended lectures in his office from 9:30 until 11:30. In the afternoons, they rode by horse to sections of the forest where Schenck conducted research or where future work was being planned. The days were long and his students teased him in song, singing “Who is the man on a horse named Punch, Riding along at the head of the bunch, Giving no time to eat our lunch?”

The Biltmore Forest School in 1901 cost $200 per year for tuition. Board ranged from $5-10 per week and $6 per month for keep of the horses.

Students lodged where they could, renting local rooms or staying in houses purchased from local settlers. Their work in the field might take them north to Michigan or on steamship trips across the ocean to Germany.

Local lodging for students. Nicknamed "hell hole".

Partly due to hard economic times for Vanderbilt, the school came to an end in 1909. By then, it was one of 22 forestry schools in the United States.

Schenck left behind a tremendous legacy, advancing the science of forestry through his research, creating tools such as the Biltmore Stick for measuring timber volume, developing a plan for sustained annual yield for the forest, building a system of roads in Pisgah Forest, constructing local schools and postal services within the forest and graduating 300 students from his forestry school.

General store and post office for students.

Today, you can visit this historic site in the Pisgah National Forest

Known as The Cradle of Forestry, 6500 acres have been set aside for this site with over two miles of interpretive trails. You can see many of the buildings used for offices, lodges, and schooling, as well as the tools and equipment for logging.

Perhaps the finest tribute to Schenck the educator came from Joseph S. Illick, Dean Emeritus of the College of Forestry, State University of New York in the forward to Schenck’s memoir. “To his everlasting credit, Dr. Carl Alwin Schenck possessed that rare quality which characterizes the superior teacher who can make education remain after all that was learned has been forgotten.”

That education is still celebrated today at The Cradle of Forestry.