In this spirit of this unique holiday season, we bring you the little-known story of "Old Christmas", a centuries old Appalachian custom wherein Christmas was celebrated on January 6. This delightful stories parallels what many of us are experiencing this year due to the pandemic, and illustrates how simpler traditions bring joy, comfort, and fellowship no matter what the circumstances.

The expression “Old Christmas” perhaps conjures a sense of Christmases past or something out of Victorian England. In reality it is a term for a tradition which is now, indeed, of Christmas past: that is, the southern Appalachian custom of celebrating “Old Christmas” on January 6, the Feast of Epiphany.

This was entirely for calendar reasons but soon became its own custom after December 25 was considered “New Christmas.”

In 1752 the British Parliament voted to change the Julian calendar, from Julius Caesar’s reign in 45 BC, to the Gregorian calendar used in certain Catholic countries. This is the calendar we still use today. However, the Julian calendar added too many leap days which, by the 1700s, was eleven days behind the sun. Thus, in Britain and the American colonies, September 2 became September 14 overnight with the time adjustment.

By the 1800s, because the Julian calendar kept falling behind the Gregorian calendar, “Old Christmas” actually fell on January 6 — which is coincidentally, on the church calendar, the Feast of Epiphany when the three wisemen visited Jesus. As often happens with governmental policy, some were unhappy that Christmas could just be arbitrarily moved.

As related to Appalachia, when the Scots-Irish immigrated here, they were either too isolated after bringing the custom with them, to know of the change or just didn’t want to adapt.

Thus, “Old Christmas” was widely celebrated in deepest Appalachia by the 1800s and in some parts even into this century.

Yet, the new Christmas, on December 25, began twelve days of celebration, still practiced in Great Britain today and known as the “Twelve Days of Christmas” lasting through Epiphany.

Some of the Appalachian traditions included “serenading” from house to house, which consisted of visiting, singing, storytelling, and even dancing. Guns were often fired and bonfires set, too — all to ward off evil spirits.

Folklore claimed that the animals spoke at midnight on January 5, Old Christmas Eve, after the Holy Spirit came to earth and the elder bushes bloomed granting them that power.

Old Christmas day itself, January 6, became a non-work day for many, like a Sunday, with church-going and family time. Like many mountain traditions in the modern age, most people have not heard about, or celebrate, Old Christmas.

Lawton Brooks, who was born in the early 1900s and interviewed in A Foxfire Christmas: Appalachian Memories and Traditions recounted this:

"A lot of people celebrated both Christmas and Old Christmas — you know, the 12 days after December 25th. Some of the old people took all those days off for Christmas. Generally, everybody would get out and go places and stay with their friends and have a big time for 3 or 4 days."

There seems to have been a solemnity to Old Christmas with church, quieter family meals, Bible readings and stockings filled with nuts and fruit. The emphasis of the season was on family and friends and sharing food and fellowship together.

Fresh game, preserved fruits, and baked goods were prepared in advance and shared. Mincemeat, made with fruit and game, was also popular and another custom brought from Great Britain. The custom of fruit cake, prepared with whiskey, was also brought by Scots-Irish settlers to America.

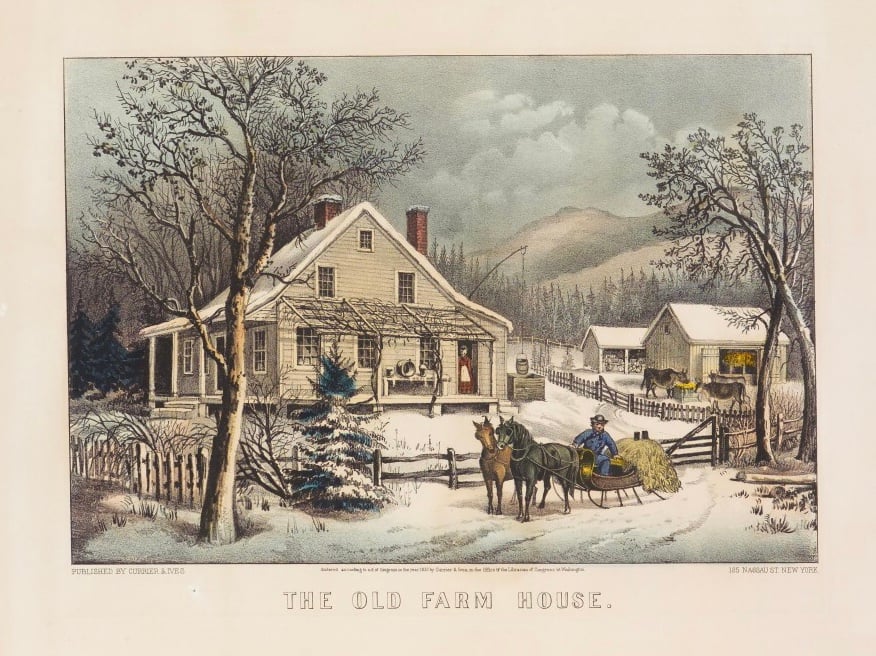

Decoration was simple and relied upon natural plants that grew in the mountains: holly, berries, evergreens, and pinecones — even accounts of sycamore seeds wrapped in foil liners, and surely mistletoe shot down from high branches. Christmas trees were generally cedar and strewn with cut-out paper decorations, yarn dolls, or cookie ornaments.

Gifts were handmade toys, warm knitted garments for winter, or other useful and homemade things.

Several accounts speak of an Irish tradition that placed a lighted candle in a window on Christmas Eve to welcome Mary and Joseph as they searched for a place to have their baby and take shelter. This welcoming spirit, and custom, lingers today in homes across the South and around the country during the holiday season.

Reflections of a quieter and traditional holiday season seem a wonderful balm to the materialism of our modern times and a cozy anecdote to the reality that so many of us are isolated by circumstance this year.

May our days be merry and blessed and our new year bright!