The holidays are a wonderful time to reflect back on our roots and family traditions. In this heart-felt essay, L. Woodrow Ross shares his memories of growing up in the rural South with his grandparents in the early 20th century. This piece is as nostalgic as it is educational, and paints a vivid picture of what life was like for homesteaders just a few decades ago. It also illustrates how quickly times change, and the value of preserving land. We hope you take the time to savor it and allow yourself to be transported back to the old South...

The house stood on a hill top that was one of the highest points in the immediate area. It was not imposing, and the remnants of paint from long ago lay in wrinkled and chipped patches on the weatherboard exterior walls.

The chimney was made of local field stone and the mortar was crumbling in the joints between the stones. It was a two-story structure and seemed huge to a small boy that had lived in much smaller houses in his short lifetime.

A porch extended across the entire front of the house and a side porch covered about half the total on that side. The old shingle roof was a weathered green and on top were lightning rods that ran along the peak of the roof and down the corners to where they were grounded to metal rods driven into the ground. The tip of the rods pointed proudly upward and small glass globes adorned the rods near the roof line. Unfortunately, one was missing where I had taken aim with a Red Ryder BB gun and later paid the ultimate price for my misguided decision!

There was boxing under the roof overhang and sometimes, starlings would nest in them when they could find a small opening to gain entry. Once I had the bright idea of climbing the spiral metal lightning rod that came down at the corners and try to catch a bird or see the nest.

When I climbed up near the nest, I felt a strange itchy sensation and was soon covered by tiny mites and had to be scoured outside in a tub to be rid of them.

On the side porch was a big wooden ice box that had a sliding top and was lined with galvanized metal. Weekly, the ice man came in a big orange truck and would leave several gigantic blocks of ice in the box to keep the milk, eggs, butter and other perishables fresh.

This house was about a mile from the main thoroughfare and I lived with my parents near the main road. When the ice man came in the summer and I was out of school, I would wait on the ice truck and when he slowed down to turn into our road, I would jump up on the back of the truck and pull the tarp back and slip into the cool, dark confines and chip off a piece of ice to suck on.

When we arrived at the “big house”, I would slip out and hide behind the huge rose bushes at the corner of the yard and wait until the man delivered the ice and when he started out, I would jump up into the truck and ride back home. As I look back now, I’m sure that he saw me and my friend Carlos, who would join me on this trip occasionally. He played the game though and pretended to never notice us.

Inside the “big house”, there were five rooms and a pantry on the ground floor.

Most of the traffic in and out were through the side porch entrance.

The immediate door was into the kitchen, which was the “heart” of the house. It contained a big wood stove for cooking and a big wood box resided beside it. It was my job to fill this box when I was there. On the back wall, there was a little pot-bellied coal heater with a coal bucket nearby. This was another chore of mine, to fill up the coal bucket from the huge pile of coal in the side yard.

There was a pantry that housed all sorts of pans, dough trays, the flour barrel, a barrel with hog feed and one with chicken feed and other assorted items.

There was a small table that held a water bucket with a dipper, a wash basin with soap nearby and a towel hanging on a nail. At the end of the table was the slop bucket that held table scraps, dish water and anything else that could be mixed with the hog feed to supplement their diet.

The egg shells from breakfast were left on the back of the wood stove to parch and later in the day they would be crumbled and fed to the chickens to get the calcium back into their systems. The chickens ran loose and at feeding time you could step outside the kitchen door and call, “Chick, chick, chick, here chick”, and they would come flying into the yard from every direction and cluck happily as they pecked at the shells and corn thrown out for them.

The hens would get laying mash in a trough to increase the yield of eggs that were eaten, and the surplus sold to supplement the meager income.

Back inside, in the afternoon, the big round-topped Philco radio would be turned on to programs like, “Just Plain Bill”, and on Saturday night, the “Grand Old Opry”. The radio sat on a small table and under the table, was a brace that held a huge dry cell battery in place. A wire ran out the window and about 50 to 75 feet across the yard to serve as an antenna. There was a straight chair that sat beside the radio and there were little ruts worn into the floor where the chair had been tilted onto the back legs and leaned against the wall like a makeshift recliner.

Moving toward the front of the house, the next room was the dining room. It held a long table with a bench on the back side and chairs at each end and the other side. There was a buffet and a pie safe and not much else. The dining room was used for all meals, there was not a table in the kitchen.

The next door opened into the big living room. There was a mantel over the big fireplace and it held a big, old pendulum clock that chimed on the hour and half hour. It resides in my house now and will pass it my youngest daughter when I am gone. There was a worn wool rug on the floor. The floor was wide irregular boards that had cracks and some knot holes, and when the wind blew hard, the air would come through the cracks and the rug would lift off the floor.

The house sat on huge stone pillars and was completely open underneath. As a matter of fact, you could look through the cracks in the daytime and see the chickens under the house at times.

The hens would lay eggs in the cool soft ancient dust under the house and I would crawl under to retrieve them. There was an old sofa and a couple of big stuffed chairs and at some point, a big bed had been moved into the room.

Over the front door was a rack made from two forks hewn from a dogwood tree limb that held an ancient Iver Johnson, single barreled shotgun with an exposed hammer. It now sits in my collection with its long, pitted barrel silent for many years. I never remember seeing anyone shoot this gun but me in later years. In those days, it hung as a piece for protection, or a reminder of hunting days gone by. The outer doors to the living room were only opened on Sunday or special occasions. There was a side door that opened onto the side porch, and again only on Sunday or special occasions.

As you entered the living room from the dining room, two doors were on the left side of the room. The one closest to the front of the house opened into a small nondescript bedroom and the other one opened into a similar small bedroom that only differed in that a stairway went up one side of the room to the second floor. Neither of the bedrooms had closets, but instead had wardrobes holding the “Sunday” clothes and shoes. The work clothes hung on pegs or nails on the wall.

As you moved up the stairs, you entered into a huge single room that was as big as the two small bedrooms and the living room that were directly beneath it.

It housed additional sleeping space and various old trunks and clothing. The lace curtains that hung on the window were yellowed and smelled of dust that was probably older than I was. One of the old trunks was used at Christmas to store fruit cakes that were baked ahead of time and wrapped and stored for the holidays.

Another thing of great interest to me was the big bags of dried fruit that hung from the rafters just waiting for a boy to fill his pockets and eat at his leisure.

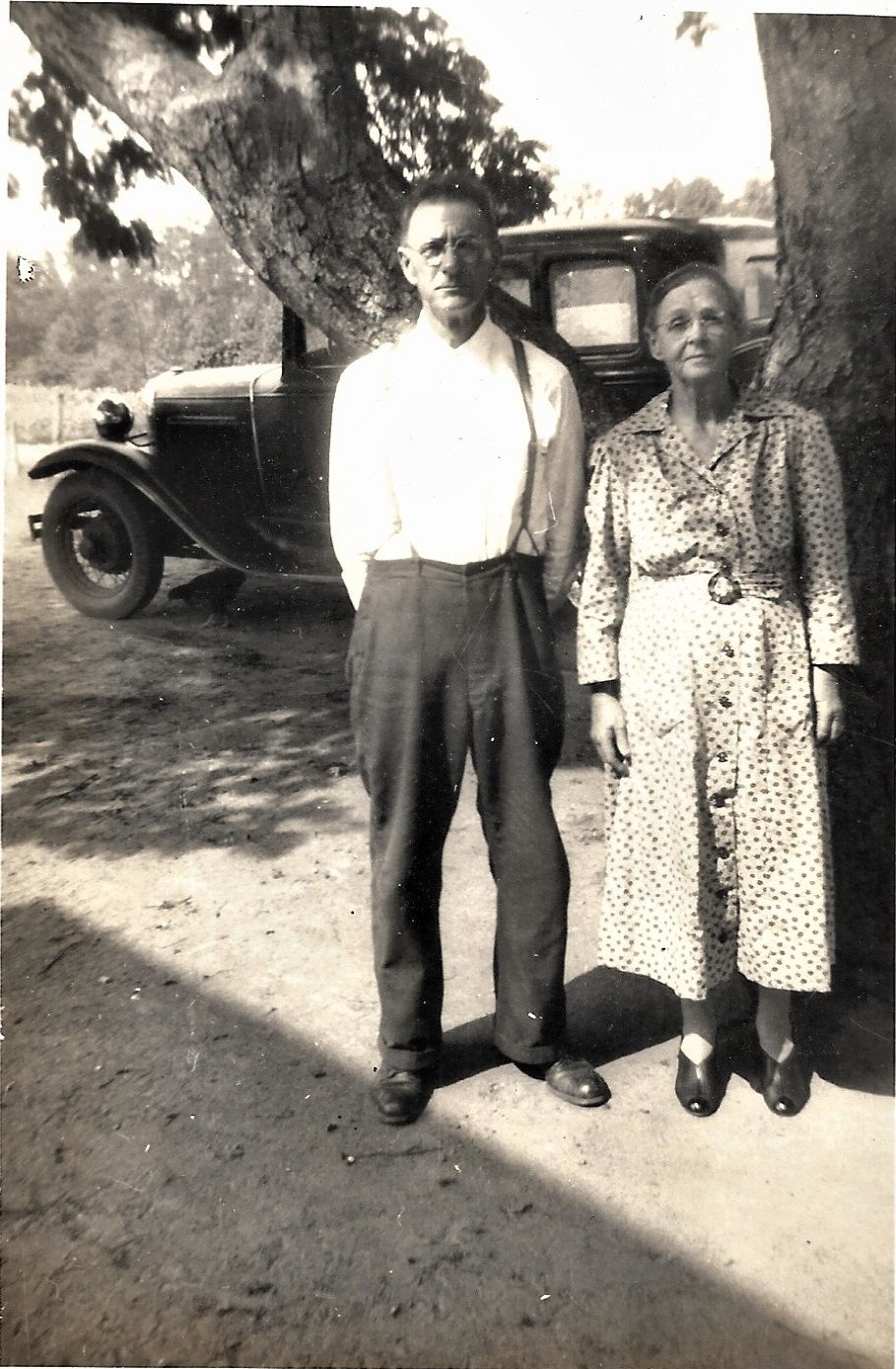

My paternal grandparents lived in the “big house”.

My grandfather was born and died there, and my grandmother lived there all of her married life. Theirs’ was a hard life with few luxuries, but it was a good, simple life. Even then, people had their problems and Grandpa slept in the small bedroom with the stairs and grandma slept in the other small room until the later years. I guess that explains the bed in the living room.

Grandpa worked hard. He was up before dawn, feeding mules and cows and milking. By modern standards, he had done a half day’s work by the time he ate his breakfast.

The days were spent plowing, planting, hoeing and harvesting from spring to fall and in the winter, wood was cut to last the rest of the year. The fireplace and the wood stove had to be fed and they were ravenous.

Grandpa would cut and split eight-foot length of wood and cross-stack it to dry and during the year would haul it into the yard to be cut to length for use in the wood stove or fireplace.

The stove wood had to be cut much shorter to go into the firebox, but the wood for the fireplace could be cut much longer. The fireplace was only used when company came. The coal heater was used on weekdays and the rest of the house was closed off to conserve the heat.

There was no heat at night and when you went to bed, you had so many quilts piled on that you could hardly move (grandma made her own quilts and the quilting frames were suspended overhead in the kitchen).

The nights got so cold sometimes that you would have to break the ice in the bucket in the kitchen to get a drink in the morning.

The bucket was filled from the well out in front of the house. It was about 60 feet deep and was covered by a well box with a frame above it that held a big pulley with a chain through it. A bucket was permanently attached to the chain and it had a weight attached to one side so that when it was lowered into the water, it would turn over rather than floating and it would fill with water to be drawn to the top.

There was a large tin tub near the well that was kept filled with water for the mules when they came in at mid-day from the fields after plowing. There was a stream in the pasture, but it was too far to go, and the mules were watered, and put into the stalls until time for plowing in the afternoon.

There was a smokehouse where hams and shoulders were hung after hog killing time, and jars of fruits and vegetables were stored in there also. I don’t know why they didn’t freeze in the winter.

The other side of the building housed various tools, and there was a shed that was used for storing cotton when it was being picked in the fall and accumulated for transport to the gin. Grandpa didn’t have a truck and the trip to the gin was an all-day job in a two-horse wagon. It was piled high with sideboards and I rode on top. It seemed to be a mile high and it was a big event to get to go to the gin.

Black folks lived on the land in a little tenant house, and helped tend the crops for board and pay and a place to grow a garden.

I remember an elderly black man named Son Tally when I was little. He lived on my grandfather’s farm. Mr. Tally had a peg leg and sometimes he would tap on it with a hammer and tell me it was itching. Another time, a black family named Richey lived there and there were boys close to my age. We played and hunted together and had a lot of fun. Those were days of segregation in the south; but fun knows no barriers, and we had a lot of good times. The boys were named L. C., L. G. and Elijah. Elijah was younger than the rest of us and one day he was aggravating me, and I broke an egg on his head and it was plastered into his hair. He was furious and I was afraid that his brothers would jump on me, but they just laughed. I guess he was bugging them too.

There was a log barn that housed the cows and mules at night and there was a loft above it that held tops for the cattle.

Tops are the top portion of the corn stalk that are broken by hand and shocked and later fed to the livestock. It would be poor man’s hay. We called it “fodder”.

The mule stalls had troughs on the wall to hold the corn at feeding time and they could be filled from outside the stables. The mules would kick the walls, and it was amazing how they would get bored and chew the timbers. It looked like beavers had gnawed the boards of the inner walls and the big log timbers!

A small blacksmith shop sat near a big ravine (we called them gullies). I would crank the bellows to keep the charcoal hot when grandpa would be sharpening plows on the anvil. They were not filed, because that removed precious metal. They were heated cherry red and pounded with a hammer into the appropriate shape and the edges were beaten thin and sharp. No metal was wasted. Scraps were saved and thrown on a heap in the shop and would be used to make hinges and other small parts as needed.

There was a big shed on the North side of the house where the wagons were kept and later the car. The only two cars they ever had was a model A Ford and later a 1939 Ford coupe. Across the back of the shed was a row of hen nests where the hens would lay eggs and sometimes varmints would steal eggs or kill a chicken. Grandpa would set steel traps and catch the varmint, which was usually a skunk or opossum. One side of the shed was a corn crib and there was an old corn sheller against one wall.

One other important building was the outhouse, which was a “two-hole” model. It was built over a pit and there was usually an old Sears catalogue and a box of corn cobs for re-cycling. It was rough in cold, windy weather and you didn’t hang around too long (I mean hang literally).

The farm covered about 55 acres and it had a small orchard, with apples, peaches and pears.

They would be canned, dried, made into pies, sold and any that were bruised by dropping on the ground would be fed to the hogs. Nothing was wasted. Food was precious and farm families knew how to make the most of what they had.

Many years after my grandparents had both died, and the last time that I was in the house before it was torn down, it impressed me that it wasn’t a “big house” at all.

It was a nice house for its day, but by modern standards, was not anything special. To a young boy it had been huge and the memories of it are as vivid today as they were in my childhood.

The house is gone now and there is a subdivision on the property. It has been bulldozed, trees cut, roads paved, houses built and it is changed forever.

It is no longer the place of my childhood, but a place that is foreign to me. I cannot bear to see it. The places that I hunted quail and rabbits and set traps for rabbits when I was a boy are like so many other things that are gone and forgotten by most.

I am glad that I can close my eyes and see the house on the hill and the bare yard that grandma swept with a brush-broom made of dogwood boughs. As long as I live, the “big house” is real, but when I am gone, it will be gone too unless someone I love can read this and see through my eyes and go again to that place of my childhood that I call the “big house”.

.jpg)